Well, I'm finished!! The thesis is officially bound and submitted. Below I've copied the final introduction and Chapter 3, which covers the English Quaker slave trade in the 17th century. I'd be happy to send the full text to anyone interested... but at 60 pages, it just seems a bit too long to post here. Email me at krg2006@columbia.edu with questions or requests. Happy reading! Katie

Origins of Abolitionism in America: The Germantown Petition Against Slavery

Introduction

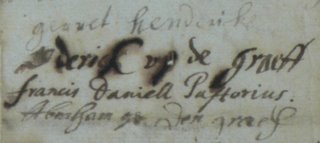

On April 18th, 1688, four Quakers in the new settlement of Germantown signed a petition “against the traffick of mens-body.” This protest against slavery was the first of its kind on the American continent and preceded the official Quaker abolition of slavery by ninety-two years. Over the past three centuries, the petition has reached iconic status in abolitionist and Quaker narratives. William Hull, an historian at Swarthmore College during the early twentieth century, calls it “the memorable flower which blossomed in Pennsylvania from the seed of Quakerism.” Samuel Pennypacker, a nineteenth century Philadelphia judge and historian, writes, “a mighty nation will ever recognize it in time to come as one of the brightest pages in the early history of Pennsylvania and the country.” Indeed, the petition has served to strengthen the modern Quaker abolitionist identity and provide deep roots for the anti-slavery movement in American history.

In 2000, the Philadelphia Yearly Meeting included a portion of the Protest in an exhibit on “Quakers and the Political Process,” compiled in celebration of the Republican National Convention’s meeting in Philadelphia. The section entitled “Ending Slavery—Striving for Civil Rights” includes the protest as part of a larger Quaker abolitionist narrative: “Beginning with the Germantown, Pennsylvania Meeting in 1688 and culminating in 1776 with all Quakers in the Philadelphia region, Friends gradually refused to own slaves.” Accompanying this history is a citation from the original Germantown Protest—with notable cuts. The curators of the exhibit chose not to cite the original references to Turks and Europe: one offends modern sensibilities, the other seems irrelevant. The revised text is attractive and accessible to a modern audience, although remnants of older linguistic conventions (and misspellings) remain:

These are the reasons why we are against the traffick of men-body, as followeth…There is a saying, that we shall doe to all men like as we will be done ourselves; making no difference of what generation, descent or colour they are. And those who steal or robb men, and those who buy or purchase them, are they not all alike? Here is liberty of conscience, wch is right and reasonable; here ought to be likewise liberty of ye body, except of evil-doers, wch is an other case. But to bring men hither, or to rob and sell them against their will, we stand against…Ah! Doe consider well this thing, you who doe it, if you would be done at this manner? And if it is done according to Christianity?…Pray, what thing in the world can be done worse towards us, than if men should rob or steal us away, and sell us for slaves to strange countries; separating housbands from their wives and children. Being now this is not done in the manner we would be done at therefore we contradict and are against this traffic of men-body. And we who profess that it is not lawful to steal, must, likewise, avoid to purchase such things as are stolen, but rather help to stop this robbing and stealing if possible.

This recent invocation of the Germantown Protest is interesting for a variety of reasons. First, it demonstrates how the Protest informs a contemporary history of the Quaker anti-slavery movement. Second, the decision to include a portion of the original text suggests that the language of the Protest appeals to a modern audience. This accessibility is rare when compared to the modern treatment of other texts within the same period. George Keith’s Exhortation & Caution to Friends, Concerning buying or keeping of Negroes, the first anti-slavery protest printed in the colonies, has received markedly less attention in the past century and while it is occasionally cited, it is rarely excerpted. Other early anti-slavery texts, including William Edmunson’s 1676 journal or Cadwalader Morgan’s 1698 letter to Friends, have been similarly ignored outside scholarly circles.

The relative popularity of the 1688 Protest raises an important question: Why has the Germantown Protest—both as a symbol and as a text—assumed such a central role in the contemporary narrative of the Quaker anti-slavery movement? What makes it appealing to a modern audience? One answer is that its place as the “first” anti-slavery protest in the American colonies comes with an inherently exalted position. But while it may have been the first “protest” against slavery, the Germantown text was not the first anti-slavery Quaker document. George Fox, while not decisively anti-slavery, defended the rights of blacks and insisted that all were equal “children of God.” William Edmunson wrote letters in 1676, in which he advocated an end to slavery. His reasoning, however, clashes with modern sensibilities. Edmunson urges Friends to introduce blacks to Jesus Christ and the Gospel and to turn them away from their otherwise “unclean” lives. Fox, meanwhile, insists that blacks are no farther from God than whites, but is uncomfortable with the idea of black “strangers” becoming a part of Quaker families.

It may be the very abnormality of the Germantown Protest that makes it so accessible to a modern audience. The language of the 1688 text is unlike other inter-Quaker texts of the same period in content, structure and style. The Germantown Protest does not follow the typical format of a Quaker document sent between Meetings. It addresses itself to “Christians,” rather than “Friends” and with minor exceptions, it forgoes Biblical references and never mentions Jesus Christ—all unusual practices for a Quaker text in the late seventeenth century. The Germantown Protest founds its anti-slavery argument on ethical and pragmatic concerns that are in harmony with, but not dependent on, belief in Christian doctrine and Quaker custom. In its direct approach to the question of slavery, the Germantowners also omit the salutary introduction to Friends that was customary of epistles sent between Meetings. In its structural style, the protest most resembles Quaker pamphlets, which were normally written to groups or individuals outside the Quaker community.

These observations raise another important question: why was the 1688 Protest different? And why were the Germantowners the first Quakers to write down and publicly denounce slave-holding and trading within a formal Quaker structure? Much of the disparity, I argue, stems from the Dutch and German backgrounds of the Germantowners. The Germantowners were foreigners in a new land; outsiders within their own Quaker community. Linguistically, culturally and ideologically they differed from the English Quakers who controlled the political and religious structures in Pennsylvania. As a result, their transition to the New World was accompanied by unique challenges and situations. This thesis is an investigation of those challenges faced by the German and Dutch Quakers who wrote and submitted what was to be known as “the first step in the fight against slavery in America.”

It is also an exploration of the origins of “revolutionary thought.” For the Protest was something new. The Germantowners critiqued the institution of slavery with a novel argument and humanized the discourse on slave-holding. As Tinkcom & Tinkcom write, “[The Protest expressed an] idea of human rights…[that] was in advance of humanitarian thought in either the Old or the New World.” Given this extraordinary achievement, it is important and interesting to investigate the social factors and individual motivations that contributed to the creation of the Protest. As J. William Frost asks in the introduction to The Quaker Origins of Antislavery, “What causes people to think of something new? Is invention primarily a personal achievement determined by individual genius or should one seek to isolate a significant cultural nexus, economic factor, or social condition?”

In the case of the Germantown Protest, the authors were responding to a variety of social, moral, economic, and political concerns. Their concerns were created by, and voiced within, the complex and unique social matrix of seventeenth century Pennsylvania, where multiple languages, conventions and values were in constant, and often contentious, conversation. For the Germantowners, the institution of slavery, and specifically the importation of black slaves, would have been a new and strange phenomenon that was an accepted convention for English Quakers. This disparity was compounded by class differences: the English Quakers who led the Philadelphia Yearly Meeting in Philadelphia were wealthier than the Dutch and German Quakers of Germantown. So while the more powerful English could own slaves, it would have been an impossibility for most of the Germantowners, nearly all of whom were skilled craftsmen who did not need slaves for their work. Of the Germantowners, only Pastorius had a relatively wealthy and educated upbringing and ironically, Ruth (1983) points out that he actually agreed to be the proprietor of slaves for the Frankfurt Company in 1686.

The partial “outsider” status of the Germantowners and their lack of need for—and unfamiliarity with—black slaves were all important factors that led to the creation of the anti-slavery protest. But circumstance alone cannot determine behavior, and the language of the protest demonstrates a strong moral conviction about the evils of slavery. The Germantowners challenge their readers to imagine themselves in a slave-like position and to take their ethics of equality seriously. They also connect the core Quaker belief in “liberty of conscience” with liberty of body, a step that provides their anti-slavery argument with a strong philosophical foundation based on Quaker theology.

This morality, however, cannot be taken completely at face value. The Germantowners were not only concerned about the treatment of blacks, but also for their own safety. During the last half of the seventeenth century, slave revolts occurred with increasing frequency. In Barbados, Jamaica and Haiti alone, slave rebellions, plots or mutinies were reported in 1668, 1674, 1675, 1678, 1679, 1683 and 1685-6. The Germantowners were aware that a slave revolt could take place in Pennsylvania and they discuss this possibility in their Protest. They also mention that their friends and acquaintances in Germany and Holland are “fearful” and “terrified” to hear that Quakers in Pennsylvania hold slaves. This reaction in continental Europe is a reminder that the Germans and Eastern Dutch would not have been accustomed to black slaves in their society. It also suggests that the Germantowners, who were desperately trying to attract new settlers from their native lands, hoped to assure their friends and families in Europe that Pennsylvania would be a safe location to settle.

In the end, no one factor or incentive can be identified as “decisive” in the creation of the Germantown Protest. Its authors were neither solely virtuous nor shrewdly political. They were influenced by strong moral convictions, social fears and political affiliations and resentments. But what they created has, over the past four centuries, become a defining, formative and inspiring symbol of Quaker abolitionism—a position that warrants merit and respect. Still, it is useful and refreshing to imagine the revered authors as people, who were subject to ordinary human fears, desires and vices. If nothing else, this reminds the admirers of this Protest (myself included) that great things emerge from imperfect people; that revolutionary concepts are often inspired by banal, unknown, or even unsettling, factors; and that revolutionary thought and action are never out of reach.

Chapter Three: Quakers and Slavery, 1688

The Germantown Quakers submitted their protest against slavery into the complex social matrix of seventeenth century Quaker Philadelphia. At the time, slavery was an accepted and common convention among the English Quakers who were in political control of the colony. The Quaker slave trade was developing rapidly and, with few exceptions, the Pennsylvania Quaker population was unanimous in its acceptance of slavery.

The introduction of Pastorius, the Krefelders and the Krisheimers brought a “foreign” group into the Philadelphia Quaker community. Slavery was one issue that was accepted by the majority of English and rejected by virtually all Dutch and Germans. As a result, it is not too surprising that the Germantowners were the first group to formally submit an anti-slavery appeal to the Quaker community. The Protest was, in many ways, “another case pointing to the different outlook upon a common problem held by the Dutch-German and the English settlers.”

The English Quaker Slave Trade

During the last two decades of the seventeenth century, the Quaker slave trade in Pennsylvania grew quickly into a prosperous industry. As Pennsylvania’s social and economic structure developed, ties with the West Indies and other trade outlets flourished and the number of black slaves in Pennsylvania increased significantly. In 1690, less than ten years after Pennsylvania was founded, William Penn announced proudly that ten slave ships had arrived from the West Indies in just one year:

The several Plantations and towns begun upon the Land, bought by those first Undertakers, are also in a prosperous way of Improvement and Inlargement (insomuch as last Year, ten Sail of Ships were freighted there, with the growth of the Province, for Barbados, Jamaica, &c. Besides what came directly for this kingdom).

The slave trade was a source of pride and a symbol of prosperity for many English Quakers who considered slaves to be necessary for economic development. James Claypoole, a Friend and slave trader who emigrated with the Krefelders in 1683 and helped organize their journey on the Concord, expressed anxiety when his slave shipment failed to arrive:

I writt to thee, to send me 4 blacks viz. A man, a woman, a boy, a Girl but being I was so disappointed in Engl[and] as not to send thee those goods thou wrote for, I could not expect thou wouldst send them…Now my desire is that if thou doest not send them all however send me a boy between 12 & 20 years.

Quaker merchants, like other slave merchants, saw blacks as a commodity. Gabriel Thomas, another Friend living in Pennsylvania, lists “Negroes” as one of many imports from the West Indies:

Their Merchandize chiefly consists in Horses, Pipe-staves, Pork and Beef Salted and Barrelled up, Bread, and Flower, all sorts of Grain, Pease, Beans, Skins, Furs, Tobacco, or Pot-Ashes, Wx, etc., which are Barter’d for Rumm, Sugar, Molasses, Silver, Negroes, Salt, Wine, Linen, Household Goods, etc.

The Constant Alice, a “non-Quaker vessel owned by William Douglas and James and Hercules Coutts,” which sailed regularly between Pennsylvania and Barbados, records that a cargo worth £134 16s. 3d. was shipped to Philadelphia in June 1701. Of that, £47 consisted of black slaves. The following year, blacks “accounted for more than half” of the cargo: £57 10s. of £114 10s. 8d.

The increase in slave shipments between 1701 and 1702 suggest that the Quaker slave trade was still on the rise at the turn of the century, thirteen years after the completion of the Germantown Protest. Although voices against slavery had intensified in the Quaker community, they were undermined by the economic structure of colonial Pennsylvania and the demand for slaves in the Philadelphia Quaker community.

Early English Quaker Abolitionists

The burgeoning slave trade had few Quaker dissenters in 1688. Still, anti-slavery sentiment can be traced back to the founder of Quakerism, George Fox. Fox emphasized that all humans were “children of God” and advocated for fair treatment of blacks, although he did not condemn slavery. In 1971, he preached to blacks and whites during a visit to Barbados and “urged Quaker masters to limit their slaves’ terms and to educate them.” His thoughts and sermons were published six years later under the title, Gospel: Family-Order, Being a Short Discourse Concerning the Ordering of Families, both of Whites, Blacks and Indians.

The existence of slavery concerned Fox on two counts: first, it made him uncomfortable to imagine himself or other Friends as slaves and he encouraged Friends to treat blacks as they would want to be treated in a “slavish Condition:”

And further, consider with your selves, if you were in the same Condition as the Blacks are…if this should be the Condition of you or yours, you would think it hard to Measure; yea, and very great Bondage and Cruelty. And therefore consider seriously of this, and do you for and to them, as you would willingly have them or any other to unto you, were you in the like slavish Condition, & bring them to know the Lord Christ.

Moral treatment, according to Fox, included allowing slaves to hold worship meetings and providing them with a Christian education. He argues that Christ “dyed for Tawnes and for the Blacks, as well as for you that are called Whites” and concludes that “therefore you should preach Christ to your Ethyopians that are in your Families.”

Fox’s second worry regarded the Quaker family. Fox saw the family as a sacred institution and feared that the presence of non-Christian “strangers” would weaken Christian practices. He reminds Friends to “see that all of your Families do keep this Sabbath, this Rest, both you and your Sons and Daughters, Men-Servants & Maid-Servants that are within your Gates; this concerns every one of you, that are Masters of Families.” He also warned Friends to be wary of bringing blacks into their quarters and while he encouraged Friends to give blacks a time to meet for worship, he did not envision a shared meeting of blacks and whites:

[It] burden’d my Life very much, to see, that Families were not brought into Order; for the Blacks are of your Families, and the many Natives of them born in your Houses...Friends…let them have two or three Hours of the Day once in the Week, that Day Friends Meeting is on, or an other Day, to meet together, to wait upon the Lord.

Fox’s two concerns, one founded on morality and the other on familial “order,” are representative of the philosophical underpinnings of the early English Quaker anti-slavery movement. On moral terms, Friends argued that slavery was inconsistent with Quaker principles of non-violence and equality. This philosophical position came to fruition in the eighteenth century with abolitionists like John Woolman, Anthony Benezet, and David Ferris. The concern for familial order, meanwhile, maintained that owning slaves was ostentatious and would promote laziness in Quaker households. With slaves to perform menial labors, Friends argued, Quaker children would not learn the virtues of hard work, simplicity and humility.

The Quaker concern for familial order came in varying degrees of prejudice. While Fox was anxious that blacks were “strangers” who did not belong in Quaker families, other Friends feared that blacks could be dangerous. Cadwalader Morgan of Merion, an early abolitionist, wrote to the Philadelphia Yearly Meeting in 1696 and asked: “What if I should have a bad one of them, that must be corrected, or would run away, or when I went from home and leave him with a woman or maid, and he should desire to commit wickedness?”

Quakers were also concerned about the moral welfare of blacks. English Quakers tended to regard blacks as unenlightened since they had not been exposed to the Gospel, and the question of how to reform them was a major question for early abolitionists. William Edmunson, a Quaker who traveled to Barbados with George Fox, urged Friends to introduce blacks to God and Jesus as a means to “Christianize” them:

Friends that have Negroes is to take great Care, to Restrain and Reclaim them, from their former Courses of their accustomed filthy, unclean practices, in defileing one another, they are to be Restrained, and Watched over, and diligently admonished in the Fear of God and brought to Meetings, that they may learn to Know God that made them, and Christ Jesus that died for them and all Men, and those things the Lord required.

Edmunson became, as Jean Soderlund writes, “probably the first Quaker to denounce slavery outright,” and Frost adds that “Edmunson’s letters to Quakers…linked spiritual and temporal freedom and raised for the first time the question whether Christianity and slavery were compatible.”

Edmunson’s worry about the spiritual welfare of blacks and Morgan’s concern for the virtue of the Quaker family are both reiterated in the Philadelphia Yearly Meeting’s first anti-slavery statement, issued in 1696: “be more careful not to Encourage the bringing in of any more Negroes, and that such that have Negroes be Careful of them, bring them from Loose, and Lewd Living as much in them lies, and from Rambling abroad on First Days or other Times.”

Slave Revolt: A Common Fear

Early Quaker abolitionists were also aware of the possibility of slave revolt. There had been a series of slave rebellions in the Caribbean during the seventeenth century, including three in Barbados, the site of the Pennsylvania Quaker slave trade. These rebellions, which occurred in 1649, 1674/5 and 1692, supported the perception of blacks as dangerous and encouraged Quaker opposition to the slave trade, albeit for practical, rather than moral, reasons. The prospect of quelling a slave rebellion was problematic for Friends because they were opposed to all forms of violence and had no organized militia.

These concerns were articulated by Robert Piles, another seventeenth century Quaker abolitionist:

I considered, also, that if all friends that are of ability should buy of them that is in this provinc, they being a people not subject to ye truth, nor yet likely so to bee; they might rise in rebellion and doe us much mischief; except we keep a malisha; which is against our principles.

The Yearly Meeting responded to Piles’ letter by writing to Friends in Barbados and requesting an end to slave importation, although the records from The Constant Alice suggest that their request was not heeded.

The fear of revolt influenced Benjamin Furly’s attempt to limit slave ownership in Pennsylvania. Furly, William Penn’s agent in Amsterdam who helped Pastorius organize his journey to Philadelphia, wrote a letter to Penn with the following request:

Let no blacks be brought in directly. And if any come out of Virginia, Maryland or elsewhere in families that have formerly bought them elsewhere let them be declared (as in ye west jersey constitution) free at 8 years end.

The heading of the passage, “For the Security of Foreigners Who May Incline to Purchase Land in Pensilvania,” suggests that Furly’s incentive in writing to Penn was a concern for the safety of his clients—potential German and Dutch emigrants—rather than an altruistic desire to end slavery (although the two are not mutually exclusive). It also suggests that Furly’s clients were concerned about the presence of blacks in the colonies and had spoken to Furly about their fears.

Since Furly’s clients included Pastorius, the op den Graeffs and Garret Hendricks—and his letter was written in 1683, when Pastorius and the Krefelders were in contact with him in Rotterdam —his letter to Penn is of particular interest. It suggests that the Germantowners may have been concerned about slavery in America even before their emigration.

They were certainly concerned about both the slave trade and slave rebellion when they wrote their 1688 Protest. The Germantowners use the possibility of revolt to supplement their argument against slavery:

If once these slaves (wch they say are so wicked and stubborn men) should joint themselves,--fight for their freedom,--and handel their masters and mastrisses as they did handel them before; will these masters and mastrisses take the sword at hand and warr against these poor slaves, licke, we are able to believe, some will not refuse to doe; or have these negers not as much right to fight for their freedom, as you have to keep them slaves?

The slave revolt was a fear shared by the German-Dutch and English Quakers in Pennsylvania. Interestingly, it proved to be virtually the only shared concern regarding slavery. Apart from the fear of revolt, the English and German-Dutch Quakers demonstrated divergent perspectives on blacks, slaves and the slave trade.

The Germantown Protest: A New Type of Abolitionism

Within the context of the seventeenth century Quaker anti-slavery movement, the Germantown Protest represents a radical shift in thinking. While the Protest shares philosophical similarities with Fox’s moral concern in Quaker Family Order and Piles’ practical fear of slave rebellion in his 1698 letter, these connections are, for the most part, superficial. Closer analysis reveals that the Germantowners had a fundamentally different perception of blacks than English Quakers. As the anti-slavery texts of Fox, Morgan and Edmunson demonstrate, the English saw blacks as unenlightened at best and dangerous at worst. Neither the “progressive” nor “conservative” English Quakers considered blacks to be the social equals of whites. The belief that blacks were the spiritual equals of whites was itself a development. Abolitionists like William Edmunson were revolutionary in their own way by proposing that blacks, like whites, were capable of salvation through belief in God and Jesus.

The Germantowners, unlike the English Quakers, articulate a distanced awareness of racial prejudice. In a parenthetical note they reference the rumors they have heard about blacks slaves being “wicked and stubborn men,” but they neither affirm nor reject this statement. Their almost sarcastic tone, however, suggests that the Germantowners are unconvinced by English prejudice against blacks.

The Germantowners conceive of blacks as the social and spiritual equals of whites. They argue that there is “no more liberty” to have blacks as slaves as it is to have “other white ones” and in their phrasing of the Golden Rule, the Germantowners add the stipulation that no difference should be made based on “generation, descent, or colour.” The Germantowners also compare the oppression of blacks in Pennsylvania to the oppression of Quakers and Mennonites in Europe. Since the oppression of Quakers and Mennonites was of a social nature, this suggests that the Germantowners believed that blacks, like Quakers in Europe, deserved to be treated as political citizens, not slaves.

The divergent conceptions of blacks among English and German-Dutch Quakers probably has less to do with the relative “morality” of each group and more to do with the rhetorical, philosophical and behavioral customs that defined the mores of each group’s homeland. The near-unquestioned acceptance of the slave trade in England and the general assumption that blacks were socially and spiritually inferior to whites made it nearly impossible for the English to even conceive of racial equality. The German and Dutch Quakers, who were not accustomed to slavery or blacks, were unencumbered by these culturally engrained biases.

A Matter of Reputation

The lack of widespread slavery in Europe did, however, create one notable problem for the Germantowners: many of their friends and acquaintances were hesitant to emigrate to a land with slaves. The “marketable” aspect of Pennsylvania was its pure wilderness and the institution of slavery worked against this image. According to the Germantowners, religious communities in Germany and Holland had gotten word of the presence of slavery in Pennsylvania and were not impressed. The Germantowners mention Pennsylvania’s sinking reputation at three different points in their Protest:

Ah! Doe consider well this thing, you who doe it…You surpass Holland and Germany in this thing. This makes an ill report in all those countries of Europe, where they hear off, that ye Quakers doe here handel men as they handel there ye cattle. And for that reason some have no mind or inclination to come hither…

… such men ought to be delivered out of ye robbers, and set free…Then is Pennsylvania to have a good report, instead it hath now a bad one for this sake in other countries. Especially whereas ye Europeans are desirous to know in what manner ye Quakers doe rule in their province;--and most of them doe look upon us with an envious eye. But if this is done well, what shall we say is done evil?…

…To the end we shall be satisfied in this point, and satisfie likewise our good friends and acquaintances in our natif country, to whose it is a terror, or a fairful thing that men should be handeld so in Pennsylvania…

For the Germantowners, who were desperate to attract more settlers from their own homelands, this was a major concern. Pastorius was still holding on to hopes that the Frankfurters would arrive, but was eager to attract other Germans to Germantown, which was still nearly all Dutch. The other Germantowners were also hoping to lure more like-minded individuals from the Rhineland, and Herman op den Graeff’s letters home had been used to advertise the tranquility and purity of the Penn’s woods.

Still, while the existence of slavery acted as a deterrent for potential German settlers, the Germantowners also found themselves unrestrained by economic reliance upon the institution, a factor that gave them practical flexibility to exercise their philosophical position. As English Quaker perceptions of blacks evolved over the next century, the economic and political structure of the slave trade proved to be the most stubborn obstacle in the fulfillment of the developing ideal of racial equality.